About Expo '58: “Roofs were shaped like helmets, others like question marks—one undulating, the next twisted in every direction... a tower spiraling upwards, pavilions that began to resemble television sets more than architectural ensembles. A delirium of color and garishness.” (from The Atomic Style)

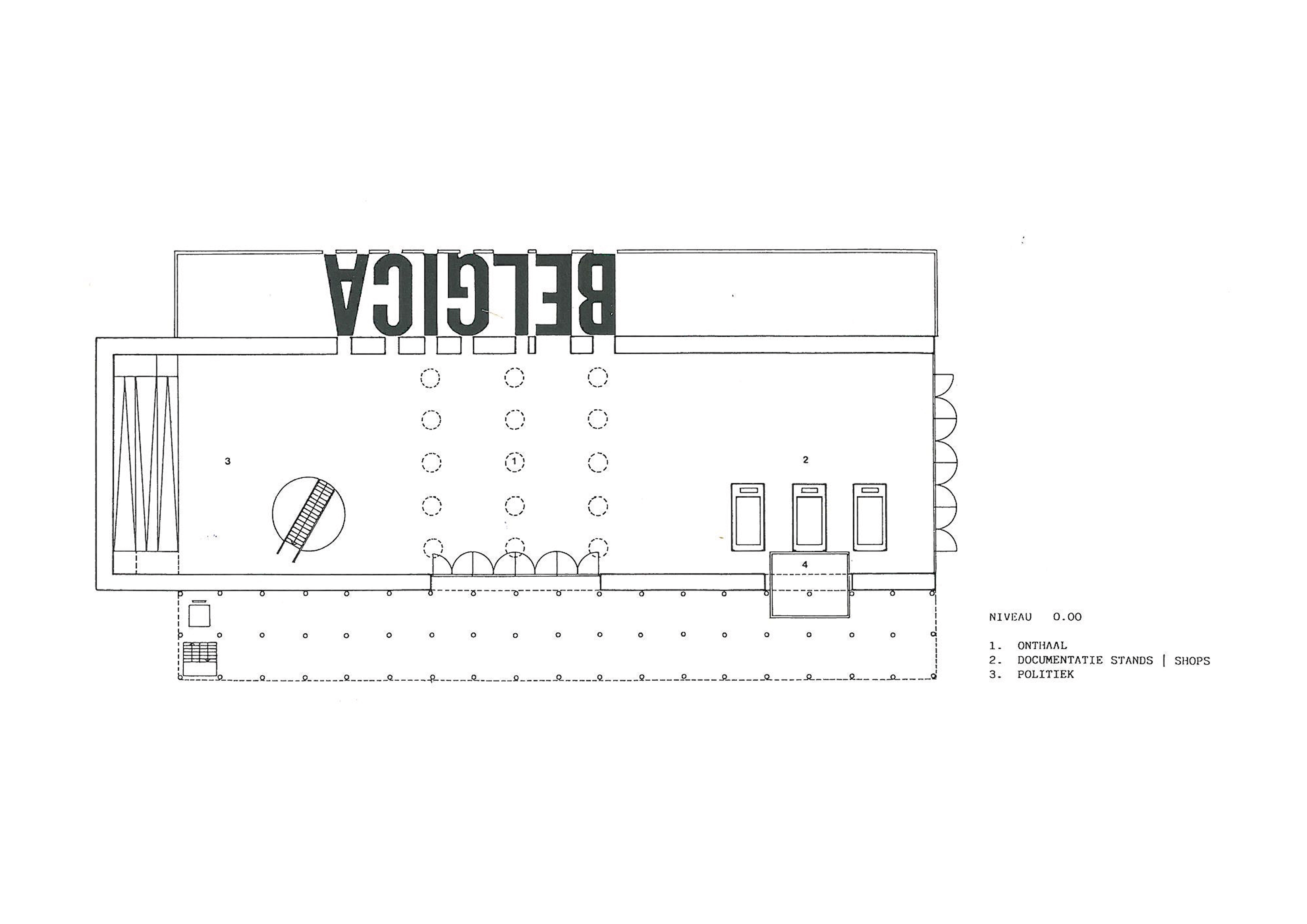

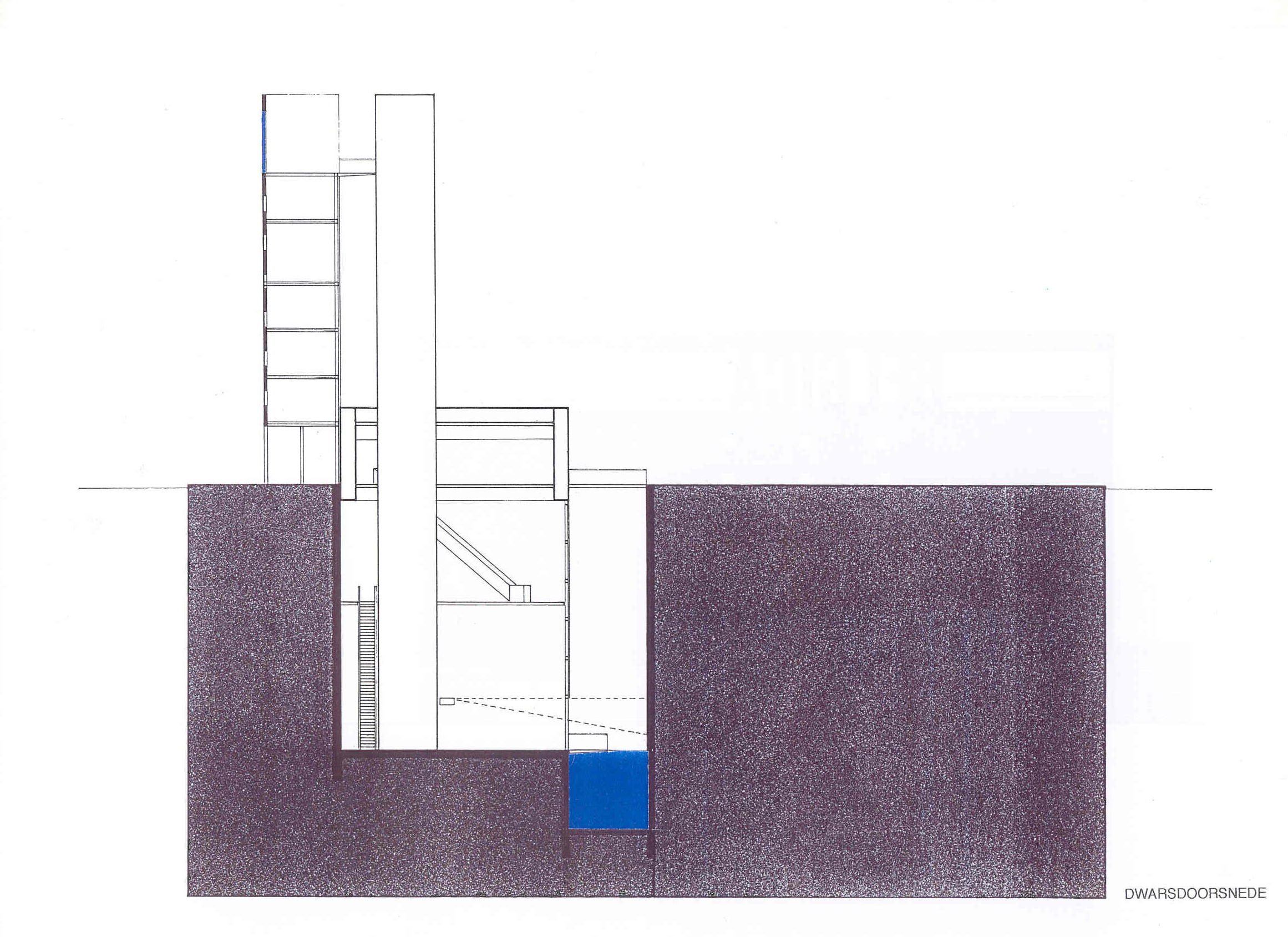

It is unbearably hot in Seville. The filter—a transitional zone between inside and outside, a forest of columns—leads us toward the entrance. Beyond it, we arrive in the reception space, at the same level: the bluestone square, a shaded low-ceilinged area with eighteen openings through which the sun casts patches of light and warmth.

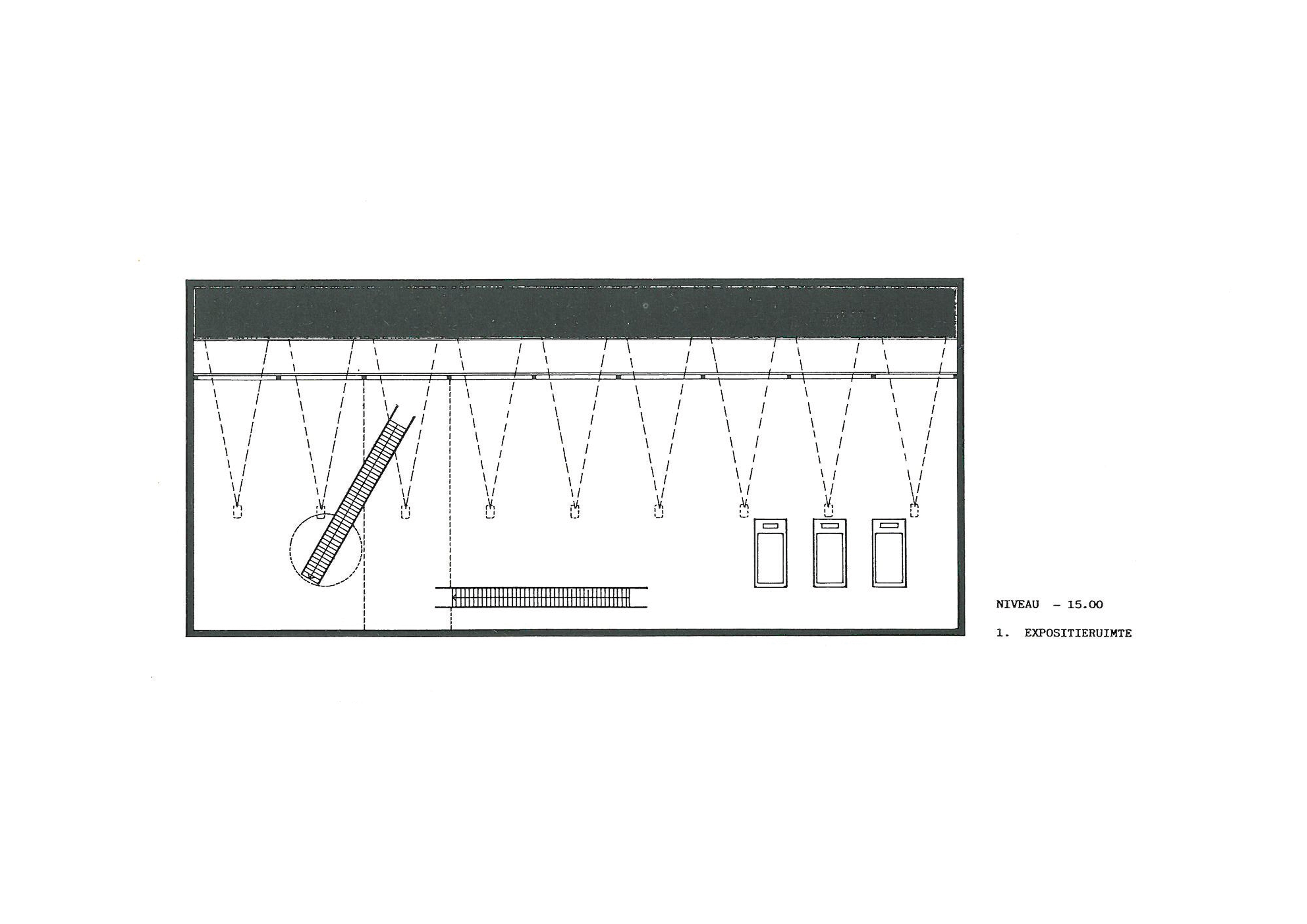

Via an escalator, we descend into the cathedral space—a tall, dark chamber without sunlight. The highest escalator faces the action. Gradually, it becomes darker and cooler. The chill of a cave, of deep water, an immense space with just enough light to see. As we move further, the space reveals itself. Halfway through, a resting point offers time and space to acclimatize. Belgium is presented here in an oasis of calm. We long for light, sun, and warmth in the south of Spain—offered only through the presence of an image: Belgium, Belgica, hovering above the water, suspended in the air. It feels cool here, without artificial air conditioning. The subtle play of scarce light through glass building blocks, the sparkle of diamonds.

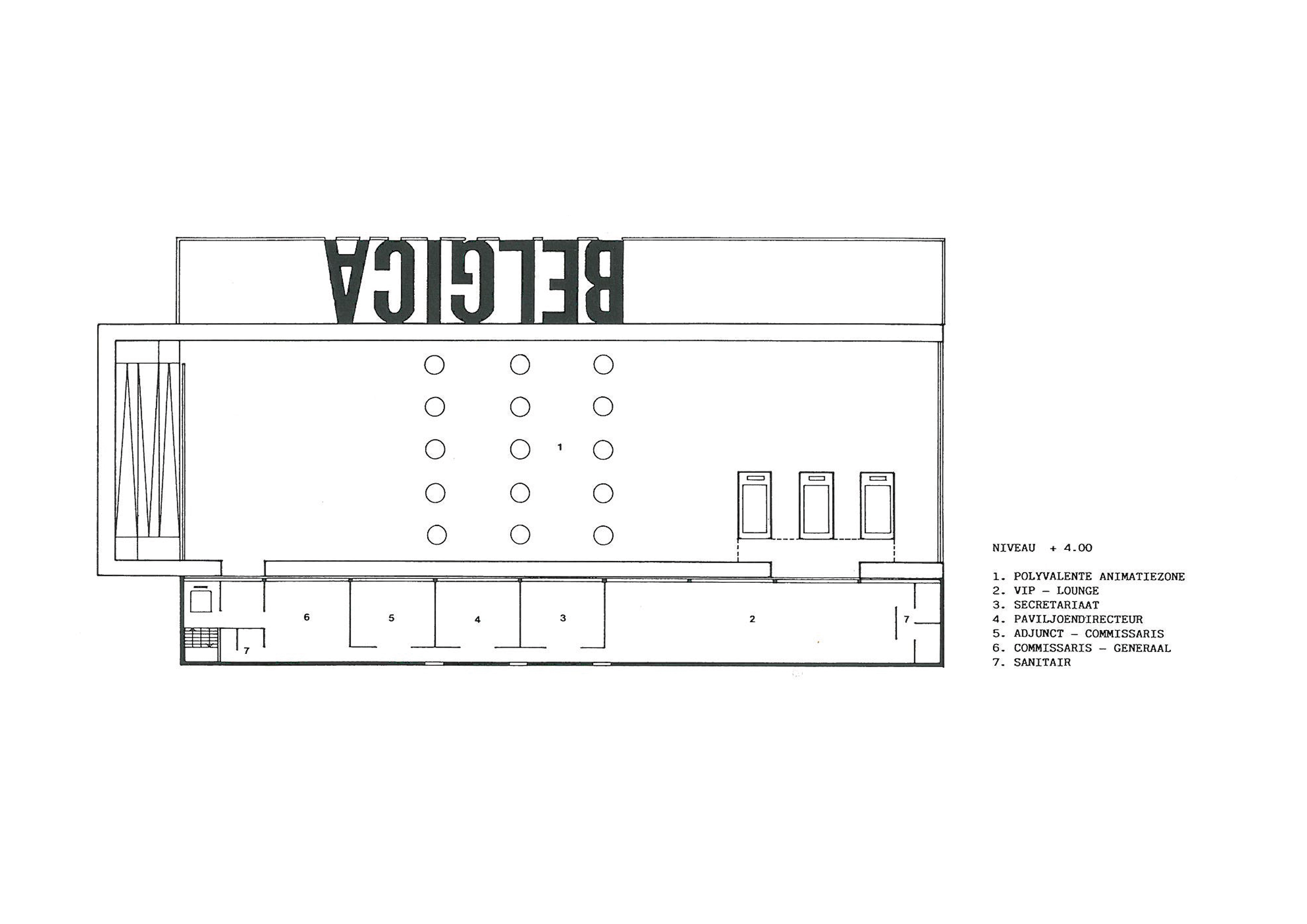

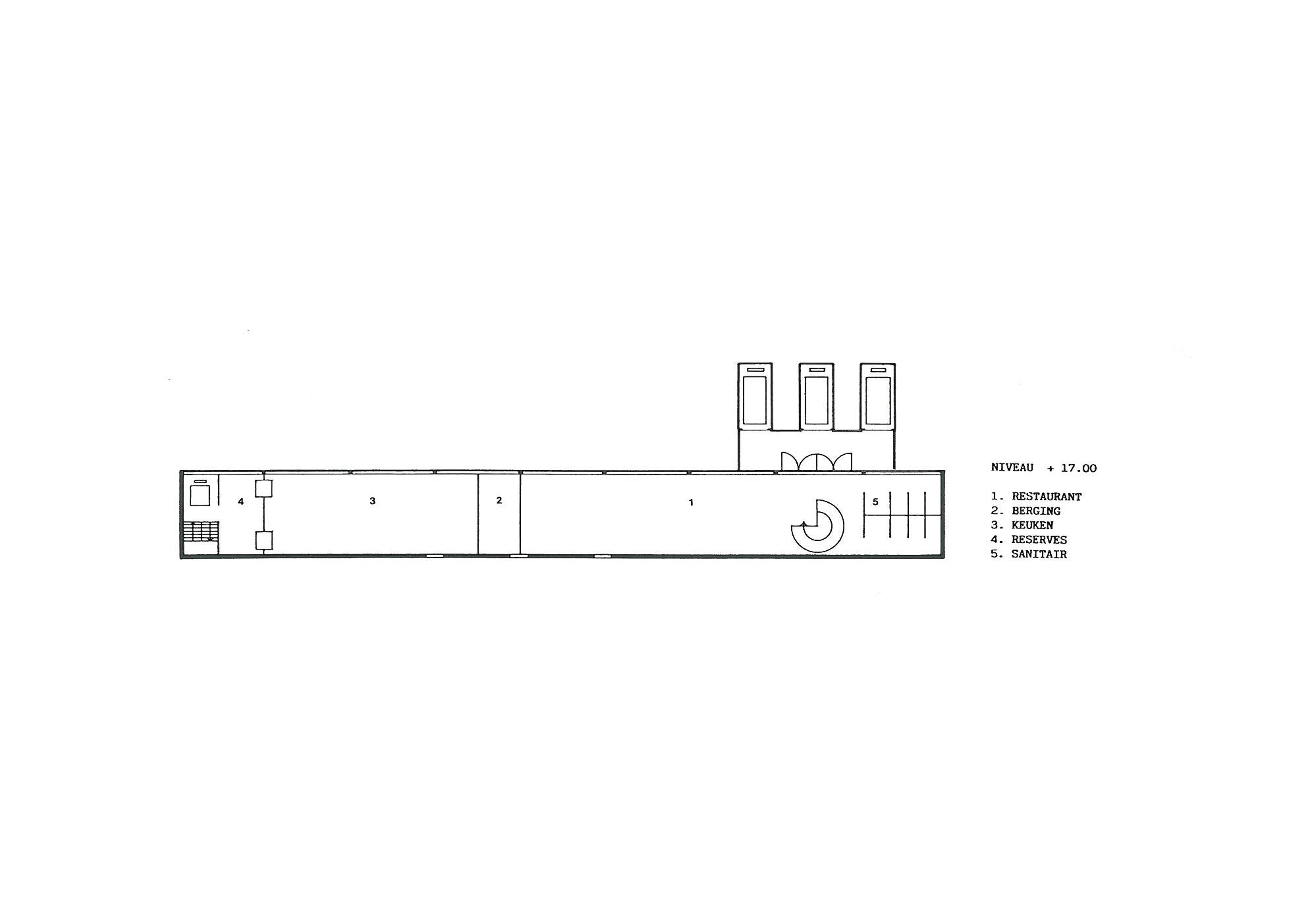

The elevators take us quickly up to the rooftop terrace, 20 meters above the activity—an overlook. Scorching, suffocating heat; we crave shade and coolness. The noise is immense. Refreshment becomes a necessity. Belgica in the air.

The elevator brings us, via the restaurant and cafeteria, to the sand square—a square enclosed by red brick walls, three meters above street level. Fashion shows, orchestras, the sand—also present throughout the rest of the site—forms a link to the outside, beyond the exhibition, into the Spanish context of holidaymaking.

Tourism—the greatest discovery?

Via a sloping ramp, we return to the bluestone square. From this square, we are expelled outward, reborn, and sent back on our way.

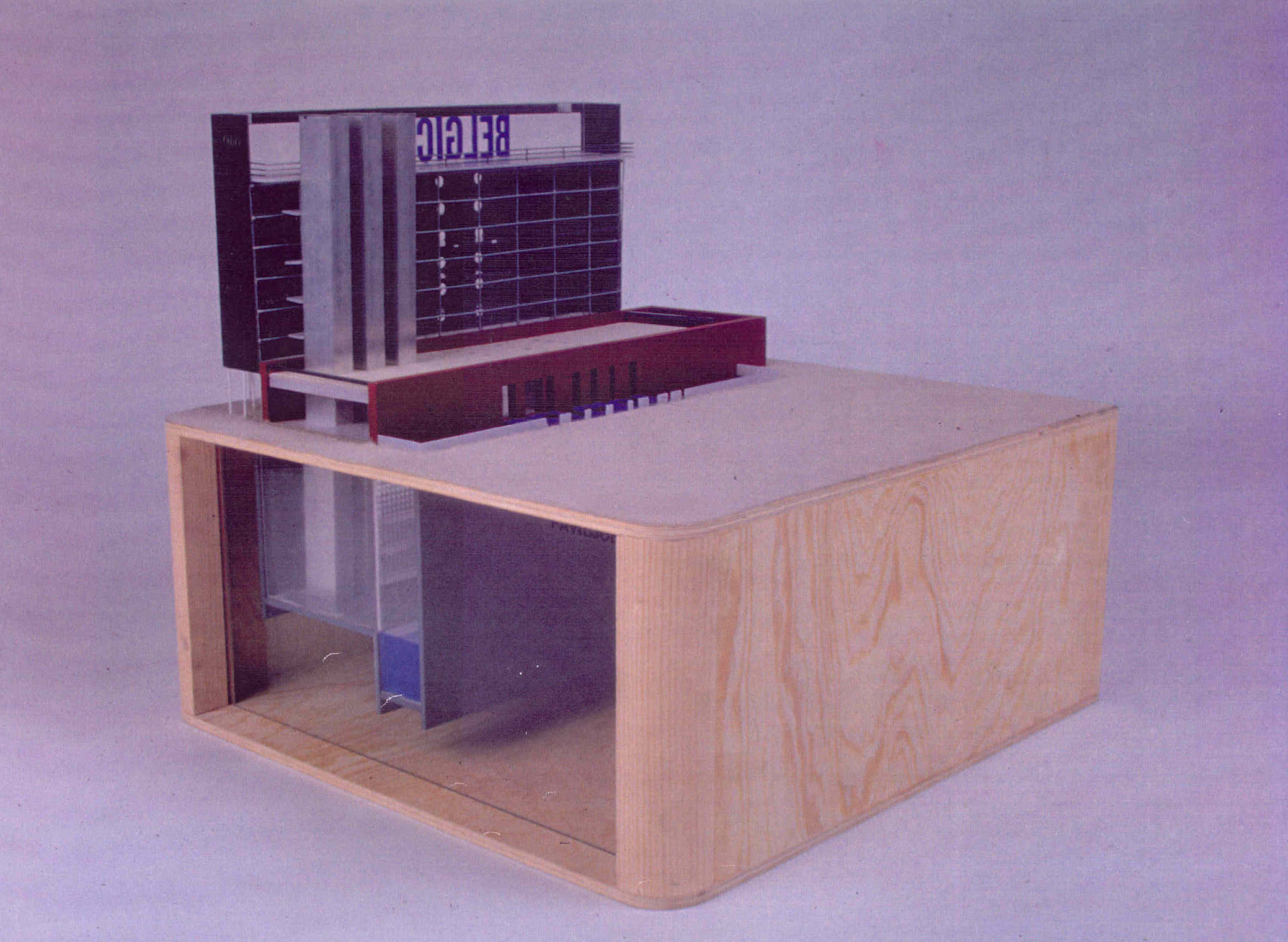

The entire composition is characterized by three entities, each with a specific spatial experience and construction method: the above-ground part typifies high-rise; the forest of columns supports the building 25 meters high. The central building is defined by a bridge structure, while the third building is constructed like a tunnel.

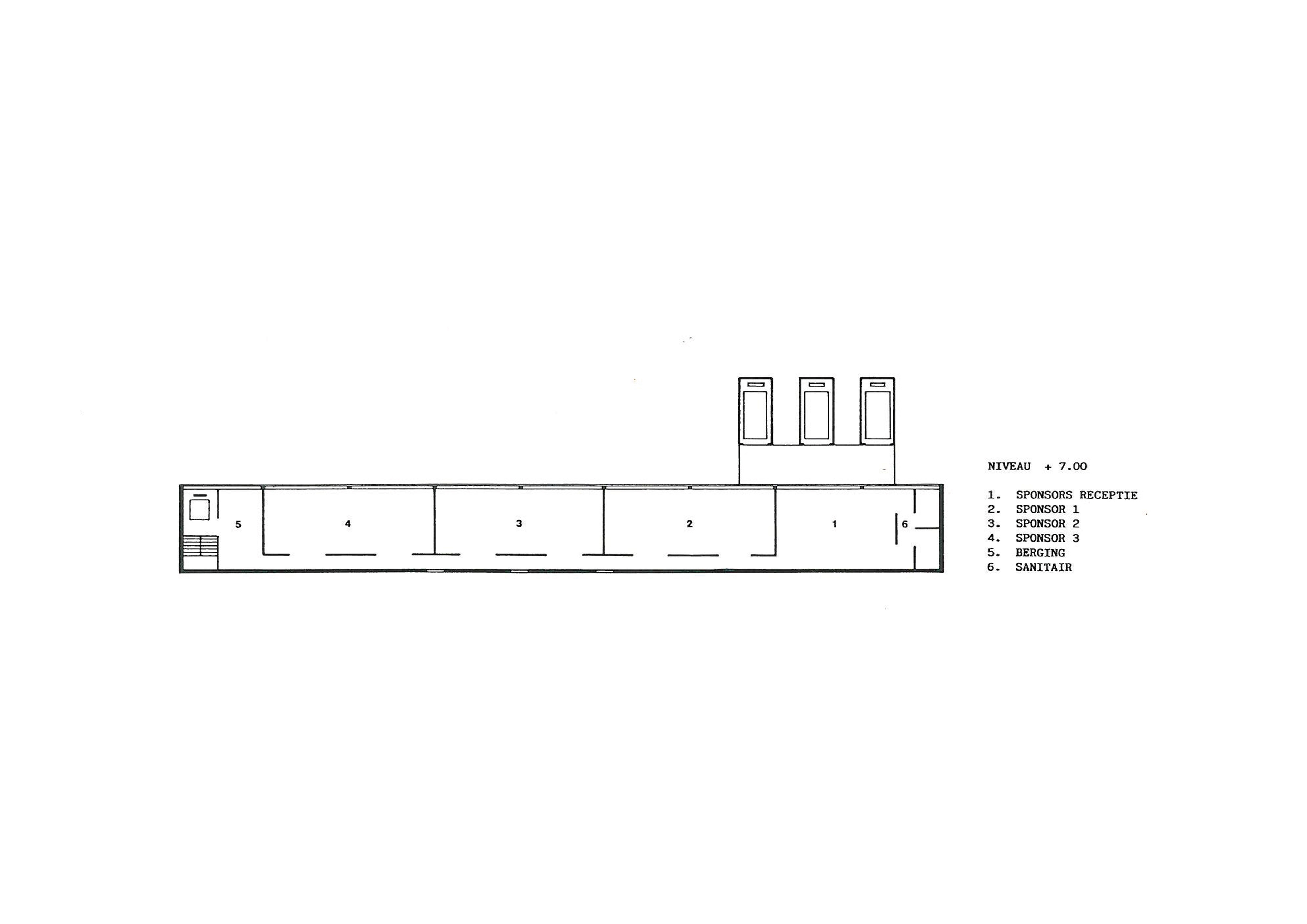

The three buildings flow into one another and form an inseparable unity. Air, ground, water. High, ground level, deep. The heart of the structure—the middle section—houses the specific functions. In the side buildings, functions vary from administration and restaurant to emptiness. The whole is strongly unified through imaginary spaces, emphasized by a perforated structure in the facade, floor, and back wall (with artificial lighting), providing a guiding thread in height, width, and depth.

In addition to space, light, climate, and sensation, constructional developments form the foundation of discovery.

Bridges, tunnels, locks, docks, canals, and dams are the cathedrals of our time. In the pavilion for Seville, such modern techniques form the basis for extreme spatial experiences.

The high-rise volume is constructed using a steel skeleton structure. Steel skeleton as a form of modular construction, allowing the building to be prefabricated in workshops. The structure has five floors and a cantilevered balcony; in cross-section: one bay of five meters. The building rests on four-meter-high columns laid out in a 2.5-meter grid—the forest of columns, marking the transition from exterior to interior. This is the only building with climate control.

The closed facade faces south and the Europalaan, casting its shadow onto the inner courtyard—the sand square. This facade is finished with horizontal blue limestone panels. Its construction includes a 20 cm thick polyurethane panel with a lacquered steel sheet on the inside, all mounted on the steel frame. The natural stone panels are also suspended from this steel structure. The northern facade is a glass-aluminum curtain wall, placed directly against the structure.

The intermediate floors and transverse partitions are constructed using prefabricated glass block vaults. Most of the building’s technical infrastructure is concentrated within the longitudinal partitions: technical service walls.

The intermediate space at ground level hangs like a bridge above the excavation. Bridge construction: assembly of prefabricated components into floor-height beams.

The roof and floor of this space are suspended between these main beams. The ground-level floor is finished with blue limestone: the bluestone square; four meters above it, the load-bearing structure is covered by a twenty-centimeter layer of sand: the sand square. The main beams rest on the diaphragm wall structure and are clad in prefabricated brick panels. Brick as cladding material—where have we seen that before?

The underground volume is realized using a diaphragm wall system with ground anchoring. Concrete diaphragm walls, 50 cm thick (subject to change after further calculation), and up to 25 meters deep, function as structural support and as soil and water retention for the construction.

A rail-mounted frame with a suspended drilling machine excavates the trenches to the required depth. The support fluid is removed, reinforcement cages are placed, and the trench is filled with concrete. The diaphragm walls are further anchored into the soil.

In the deepest part of the underground area, a water channel regulated by pumps is present.

This building is a concept designed for the hot climate of Seville; therefore, constructing such a building in Belgium is unnecessary. Only the high-rise section could be relocated to Belgium as a souvenir. The excavation remains in Spain—where it belongs.

CREDITS

Second prize in the design competition for the construction of the Belgian pavilion at the 1992 World Expo in Seville

Team: Frank Delmulle, Luc Reyn

PUBLICATIES

SAM, 1990 / CAO, 1990 / PLUS, 1990: 'Wortegemnaar net niet naar Wereldexpo 1992'